Director’s Note: What will Ian do to Sarasota Bay?

First off, I hope everyone came through Ian without too much damage. Our thoughts go out to Jennifer Carpenter, a member of our Policy Board who represents FDEP from their Fort Myers office. As you know by now, impacts increased from north to south, and while my neighborhood had damage from hours of tropical storm force winds and hurricane level gusts, we did not have the hours on end of hurricane force winds like southern Sarasota County, Charlotte County, and especially Lee County. As happens after these storms, people will correctly be focused on efforts to recover from the impacts of these events.

So where does the SBEP fit in, after Ian? While the health of the bay may be secondary to other issues right now, it won’t stop being a concern for our neighbors. What do we expect to happen to our water quality? Well, it will most likely deteriorate quite substantially over the next week or two, and maybe longer. This paper was written by myself and my colleagues at SWFWMD and FDEP when we investigated the impacts of 2004’s Hurricane Charley on the water quality of the Peace River and Charlotte Harbor. One of the biggest surprises was that the stench of the water that was so evident throughout the river and on the harbor itself was more associated with vegetative debris from wind damage, rather than sewage overflows or other events. All the green foliage from trees was washed into the creeks and bays and resulted in spikes in bacteria, nutrient loads, and subsequent crashes in levels of dissolved oxygen in the days and weeks afterward. Proximity to the eyewall of that hurricane was a better predictor of water quality problems than the number of sewage treatment plants or septic tanks in the watershed. The water quality in Charlotte Harbor took about 2 weeks to recover to pre-storm conditions, while in the river itself, it took 2 to 3 months to recover. Driving around the watershed after Charley, if you looked out the window and saw no leaves on the trees, you knew it would smell like rotten eggs when you rolled down the window. When it smelled that bad, you knew you’d find no oxygen in the water, and with no oxygen, you either had fish kills or – if lucky – you found out that fish had left the area.

The onset of poor water quality will take a few days to manifest itself, most likely. The immediate impact will be highly turbid water from stormwater runoff. That sand and debris will settle out. But the leaf material and dog poop and lawn clippings across our landscape that washed into our bay will be food for bacteria to feast upon over the next few days. There are also substantial wastewater overflows that have just occurred, including one not more than a few blocks from my house. Expect bacteria levels to exceed levels safe for swimming and wading for the next few days to weeks. Expect the water to start to look bad, and smell worse, over the next few days, as bacteria levels build up in response to loads of organic material washed into the bay from wastewater overflows and stormwater runoff. Areas with better flushing will recover first, followed by areas farther away from passes. Palma Sola Bay and Little Sarasota Bay will likely have the worst water quality for the longest period of time, due to the long residence times of those two systems.

But by mid-October into November, this will most likely get better. As this pulse of organic material is processed in the bay’s water, we should be in a better place as we move into the dry season, and as runoff decreases and water temperatures start to decline. November is typically one of the driest months of the year, and a time when summer to fall temperatures start to decline.

Keep in mind a few things – a cleaner bay is a more resilient bay, and the better our water quality is, the better we will be able to handle this and future events. Next, keep in mind that mangroves are our friends – they won’t stop an 18-foot storm surge, but they will knock the waves down on top of any surges, and they hold shorelines in place, and their leaves release compounds that help keep harmful algal blooms under control. When we take care of them, they will help to take care of us. But if our first response to mangroves is to chop them down, then don’t be surprised if your seawall gets compromised or overtopped by waves from the next storm.

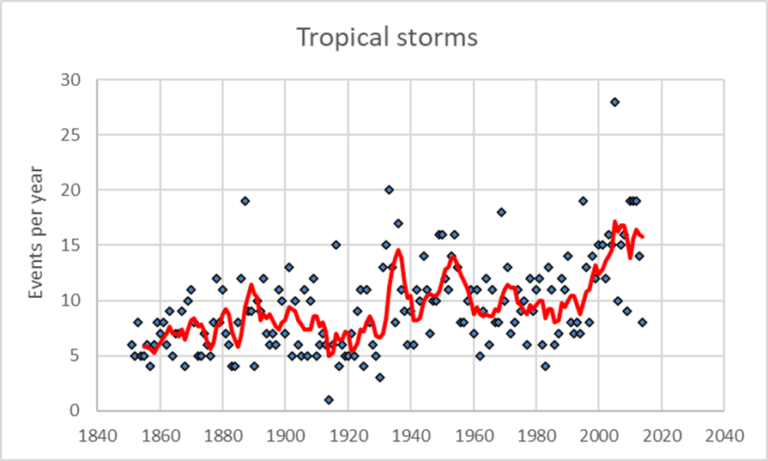

Finally, this was not a one in 100-year or one in 500-year event. It’s not anyone’s fault for thinking that way if this isn’t their specialty – it’s the fault of people who aren’t updating our expectations. With that in mind, here is a plot of the number of tropical storms and hurricanes in the North Atlantic Basin over the past 150 years (courtesy of the National Hurricane Center) with a red line representing the five-point moving average:

Figure 1: Number of tropical storms and hurricanes in the North Atlantic Basin over the past 150 years.

Note the general increase in the number of tropical storms per year in the North Atlantic over the past 40 years. We’ve always had tropical storms, and we had quite a few in the 1930s. But our trend the last 40 years is for increasing numbers above and beyond prior periods of elevated storm frequency. More worrisome is the trend for “major” hurricanes in the North Atlantic basin, those of category 3 or higher, as shown below:

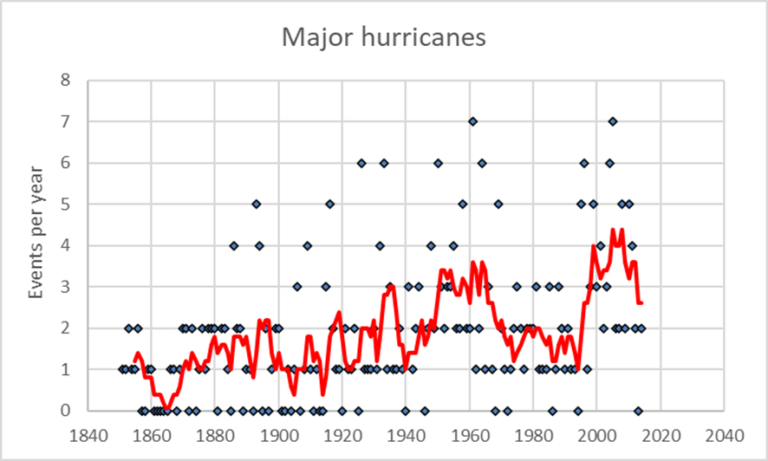

Figure 2: Trend for “major” hurricanes in the North Atlantic basin.

We’ve had major hurricanes recorded since before the Civil War! But note the overall pattern over last 20 years. We had 7 major hurricanes in the North Atlantic in the early 1960s, just like in 2004. And we’ve had multiple years with four or five major hurricanes more than one hundred years ago. But note the general pattern, illustrated by the red line – the frequency of major hurricanes is higher on average the last 20 years than any prior period, going back 150 years. Also, note that in the first part of this record, we had quite a few years with no major hurricanes recorded – years with values of zero. But in the latter part of the record, we hardly ever have had a year without a major hurricane in the North Atlantic Basin.

Why is this happening? Because hurricanes are basically heat engines – they take the thermal energy contained within warm water and warm moist air and convert it to the mechanical energy of wind and waves. And as our air and water become warmer, we are priming our oceans and coastal waters with more thermal energy - more fuel. It’s kind of like red tide – humans don’t cause red tide, we cause them to be worse by providing the fuel (nutrients) that can make them bigger, more intense, or longer lasting. Similarly, humans don’t cause hurricanes, but we seem to be causing them to be worse, by increasing the fuel (warmer air and water) that can make them worse.

Like red tide, we will never stop hurricanes. But we can do things to stop making them worse. In the meantime, it’s important to help make this bay and its shoreline and watershed as resilient as possible, because we’re not going to have to wait 500 years for the next Ian to come knocking on our door. For now, SBEP will be out on the water and along the shoreline for the next few days documenting the impacts of Ian on different types of shorelines, as well as documenting the extent of storm surge – which should allow us to better calibrate our storm surge models.