Director’s Note: Future challenges

We are entering 2024 with a bay that has the best water quality at any time over the past 8 to 10 years. If sustained, this will meet our proposed goal to get our water quality back to the condition it was during our proposed “reference period” of 2006 to 2012. This is not due simply to the very dry conditions we had in 2023, as our water quality has been good enough to meet our previously established water quality standards (for nutrients) for the years 2020, 2021, and 2022 – we don’t even have 2023 numbers calculated yet!

This hasn’t occurred due to chance alone, it seems to be associated with the response of this bay to the ongoing >$300 million investments in stormwater retrofits, wastewater upgrades, and public education about how to live a more bay-friendly lifestyle. We are very proud of what is happening here – and you should be as well.

However….we don’t want to have spent all this money, to bring this improvement about just to see it slip away from us again. And the next 30 years will be different from the last 30 years, because at least four things have changed, based on data, not models:

- The air temperature these last two to three decades is warmer than it was during the period of 1900 to 2000

- The water temperature in the Gulf of Mexico has been increasing for the past three to four decades

- The water temperature in Sarasota Bay is warmer now than it was in the 1970s and 1980s

- The rate of sea level rise (SLR) over the past 20 years is about three times the rate documented over the years of 1947 to 2000

The last finding, the increased rate of sea level rise (SLR) over the past 20 years appears to mostly be due to thermal expansion, rather than melting glaciers and such. By definition, temperature is “…a measure of the average kinetic energy of a molecule or atom.” The more energy applied to a mass, the more kinetic energy it has (by definition) which means the atoms or molecules bang into each other more often, increasing the space between themselves. Imagine a cup full of marbles, and then you shake it – some of the marbles will exit the cup because they don’t have enough “space” in the cup once you added energy by shaking it. This is why a hot air balloon rises up into the sky – the thermal energy added via a propane burner causes the molecules that comprise “air” to bang into each other, increasing the space between them and lowering the density of the air in the balloon.

Warm water expands upwards – which gives us the acceleration in rates of SLR – just the same as warm air expands outwards, which gives us a hot air balloon ride.

But how much SLR are we expecting, and frankly, so what?

Our estimate of SLR is not from model scenarios but is based on the last 20 years of data from the St. Pete gage. You can download the data yourself, and plot it out over time, which is what we did. We then ran that analysis by our Technical Advisory Committee (TAC), and have summarized it as follows:

Over the past 20 years, the average sea level has increased by about 6 inches, or 3 inches a decade – roughly triple the long-term average. If this rate persists for the next three decades, it means that sea level in the year 2050 will be about 9 inches higher than in the year 2020

As a quick way to summarize what this might mean for us, our tidal range is about 18” here, on average. Which means, in the year 2050, the average sea level will be about where today’s high tide is, and the average high tide in the year 2050 will be about 9 inches stacked on top of that.

What do we expect will happen with that? Will the Van Wezel be submerged by high tides in 30 years? Not likely. Will the Selby Library or the majority of Cortez be submerged by high tides? Again, not likely. However, we already get “blue sky flooding” in areas like Bradenton’s Riverview Boulevard at 22nd Street, and in parts of Longboat Key Village. What is more likely than anything else is that in neighborhoods along the water, we will get more street flooding, in more places, particularly when it rains on a high tide. One-way valves on stormwater outlets may reduce street flooding when it’s ONLY a high tide, but when it’s raining AND a high tide – they won’t likely be able to help as much as we’d like.

For the bay, the biggest loser – in terms of habitat – is likely to be mangroves, particularly in those areas where we have built, or where we are going to build, seawalls. This is due to the issue of “coastal squeeze”. Basically, mangroves occur along the shoreline in that belt of submerged land between Mean Low Water (MLW) and Mean High Water (MHW). Well, what happens if both MLW and MHW increase by 9 inches? If there is a gentle stretch of land next to the mangroves with a shallow slope, perhaps they can migrate “upslope”. But what if their ability to migrate upslope is blocked by a seawall? Can’t they just “adapt” somehow?

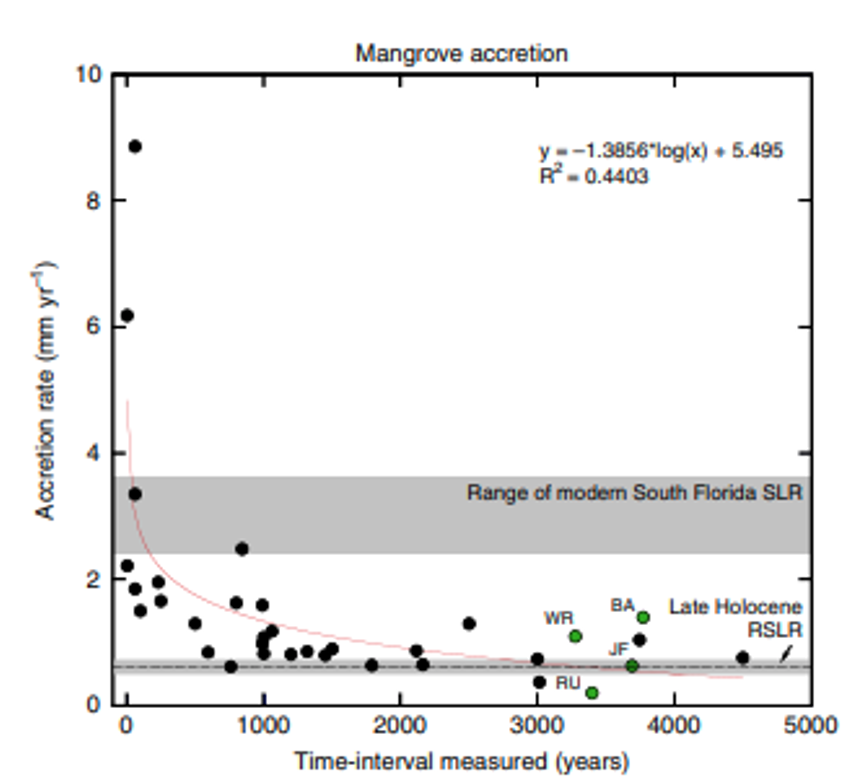

Well…a 2019 paper by researchers with the USGS and Harvard suggests that we don’t really know if mangroves can adapt to such a rate of SLR. We don’t know, in part because over the past 5,000 years, they’ve never had to deal with such a rate. The graphic below shows the rate of “accretion” or soil increase in mangrove forests over time. You can date sediments in various ways, which allows us to figure out what the rate of SLR has been over time. What this graph shows is that the rate is now higher than it’s been at any time over the past 5,000 years. So, can mangroves handle the accelerated rates of SLR that we are exposing them to? Who knows – they certainly haven’t experienced it over the past several millennia.

This gets to another point – sea level has certainly changed, dramatically so, over time on this planet. 20,000 years ago, humans lived on this planet, and the sea level was about 300 feet lower than it is right now. Three hundred feet! Anyone who doesn’t know this should know this – humans have been around when our planet looked very different than it does now.

But…how long has civilization been around? The ancient Egyptians first formed complex societies about 4,500 years ago, similar to the start of organized societies in present-day China, the Minoans and about 1,000 years before the Olmec civilization in Central America. The Sumerians in Mesopotamia date back a bit farther, maybe 7,000 years ago.

Generally speaking, the most ancient civilizations on Earth haven’t been around much longer than the far right end of the x-axis on the plot shown below. Which means, while humans may have been around on this planet when the sea level has been much lower than it is now, both modern and ancient civilizations have not.

For most of the time that civilizations have existed on this planet, our rate of SLR has been much lower than what we are seeing lately. Can mangroves adapt to these higher rates of SLR? We don’t know, but don’t bet on it.

And so if we don’t come up with strategies to allow mangroves to migrate upslope with accelerated rates of SLR, we may very well end up losing them, along with the ecosystem benefits they provide.

In a paper I was involved with working on this issue for the Tampa Bay Estuary Program, we estimated that if we didn’t allow for this upslope migration of mangroves, we could very well lose mangroves in many areas (where seawalls prevented such migrations) by the year 2075. Will that happen? We don’t know. But if we think mangroves are important to our wildlife and fisheries and water quality and as a protective feature of our shorelines – we’re kind of running a planet-wide experiment while sitting in the test tube.

Hopefully we can test out and implement strategies that can help us to preserve the mangrove fringes we have in Sarasota Bay – which have likely existed here as long as the oldest civilizations on the planet.