Director’s Note: 2022 seagrass map results – how are we doing?

Earlier this morning, the Southwest Florida Water Management District (SWFWMD) released its preliminary seagrass map results for 2022. These results are used by the SBEP as a holistic biological indicator of ecosystem health, similar to how seagrass maps are used in Tampa Bay, the Indian River Lagoon, the Chesapeake Bay, and worldwide, actually. A big shout out to the District and their project manager, Dr. Chris Anastasiou.

So how’d we do? In a word, “mixed”. First the bad news – our coverage decreased by 5%, compared to 2020, a decline of 577 acres. This builds on prior losses, such that we are down 3,511 acres bay wide, compared to our peak in 2016, a decline of 26%. This is further proof of the need for Sarasota Bay to act more quickly to reduce our watershed nutrient loads, and supports the logic behind our preliminary nutrient load reduction target of 20%, which we laid out to our Technical Advisory Committee (TAC), Citizens Advisory Committee (CAC) and Management and Policy Boards about a year ago.

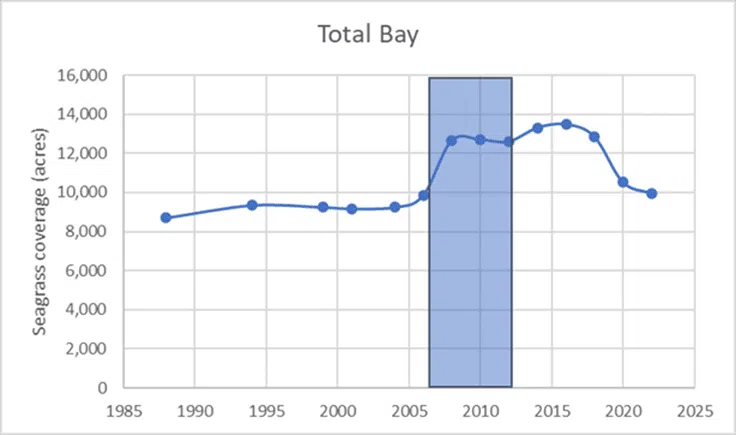

This plot shows the overall seagrass coverage in Sarasota Bay since 1988, the first year with good quality maps -

The “bad news” here is the obvious decline in coverage since 2018. Some of the “good” news in this same plot is that coverage is still higher than it was in the late 1980s and 1990s. This is an important point for folks to know – Sarasota Bay is not as healthy as it was 10 to 15 years ago, but it is healthier (better water quality and more seagrass) than it was 30 years ago.

The blue box in this plot represents the 2006 to 2012 time period. Those are the years that we proposed for our “reference period” approach to developing our pollutant load reduction strategy. As you can see, 2006 to 2012 was a period during which we had substantial increases in seagrass coverage, along with lower nitrogen concentrations in the water, lower levels of phytoplankton, and lower levels of drift macroalgae. It was also, a period of reduced nitrogen loads to our bay – 20% lower than loads during the subsequent years of 2013 to 2019. Basically, if we reduce our nutrient loads by 20%, we believe we can create the foundation that will allow us to have a healthier bay, and to prevent us from turning into the next Indian River Lagoon. It won’t be easy, and it won’t be quick. Work done in the Chesapeake Bay and elsewhere suggests that multiple years are required between reducing pollutant loads and the improvements in water quality and increases in ecosystem health. It’s kind of like your IRA or 401(k) – the numbers go down a lot quicker than they increase, due to feedback mechanisms. But like your IRA or 401(k), positive results are possible, with a continued commitment to being smart about your choices.

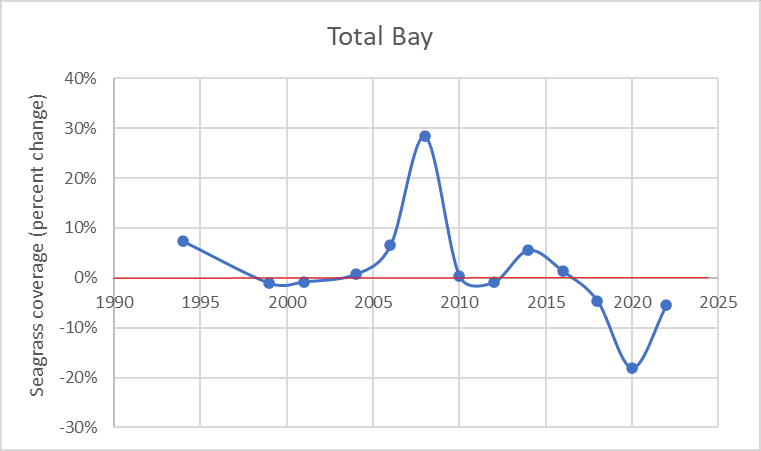

We are not in the same category of ecosystem dysfunction as the Indian River Lagoon, which is the epicenter of record-breaking manatee mortality (due to starvation from loss of seagrass) these past two years. But we are almost halfway there – in terms of the percent decline in seagrass coverage. The 2022 numbers are not great news, but there is some reason for optimism. For example, the plot below shows the trend in gains or losses in coverage over time, in terms of the percentage change from the prior mapping event, with the red line separating periods of gains from periods of losses –

If you look at the period of 2014 to 2020, there is a downward trend year to year up to 2020, including our worst results – an 18% decline between 2018 and 2020. The uptick in the line between 2020 and 2022 represents a lower rate of decline, not a gain. But it suggests that there is some room for optimism, in that the rate of loss has lessened, not increased. If 2024 numbers follow this most recent pattern, we could potentially see an increase in coverage – fingers crossed – in the not-too-distant future.

Why should we care about this? Because our quality of life, our economy, and our wildlife heritage are at risk, not just here, but across the state. Our results are not great, but it could be worse. Tampa Bay is now down a similar percentage as us from its peak values since 2016 – a 28% decline (we are down 26% over that period). But their 2020 to 2022 percent rate of decline is more than twice ours, and two parts of Tampa Bay had declines of more than 30% over the last two years alone. The Tampa Bay Estuary Program (TBEP) is convinced that more needs to be done – quickly – to reverse this downward trend in what was not that long ago a nationally-recognized success story.

Are we on the right track here in Sarasota Bay? We’re getting there. Across our watershed, nitrogen loads from wastewater overflows peaked in 2018 – perhaps a value higher than even what happened after Ian came through in 2022. Our water quality in 2021 was better – across the bay – than at any time over the past 5 to 15 years. And our local governments have publicly committed to spending massive amounts of funding for wastewater and stormwater projects over the next 5 to 10 years – which is what we’ll need to do to get our pollutant loads down to what they were during the time when this was a healthier bay.

To be sure, we not only want to reduce our pollutant loads, we also want to increase the “assimilative capacity” of the bay to increase our ability to accommodate higher loads. For example, the SBEP is in favor of increasing the amount of oysters and clams in the bay. But we can’t ONLY dump clams and oysters into our bays, thinking we can restore water quality without the much more expensive actions needed to reduce pollutant loads to those same waters. And while there is room for seagrass transplanting as a tool to test various management questions, keep in mind that the more than 40 square miles of seagrass meadow increases that occurred between 1999 and 2016 across SW Florida occurred via natural expansion in response to improved water quality, not SCUBA divers planting seagrass.

Also, we need to do a better job not only with stormwater and wastewater, but with protecting our remaining mangrove forests. Recently, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) released a consent decree on a case of illegal mangrove trimming along the mainland shoreline north of Longbar Point. This event – clearly out of compliance with permit conditions - reduced the number of healthy mangroves along our shoreline. Not only were trees illegally trimmed, but much of trimmed vegetation was left to decompose in the shallow waters of the bay (also clearly out of compliance with their permit) which increased nutrient loads to the bay, likely increased levels of bacteria in those same waters (which became, in effect, an underwater compost heap) and probably lowered levels of oxygen in what is a prime nursery habitat for juvenile fish. That is moving us in the wrong direction in terms of maintaining our water quality and our ecosystem health. If you care about water quality, you can’t have actions like that become the norm along our shoreline.

I’m an optimist, and I still think that we are on the verge of turning this bay around. But getting there won’t be easy, and if we don’t want to turn into the next Indian River Lagoon, then we need to do more, more quickly, to keep that from happening. Improvements at the Bee Ridge Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP), the actions taken to shut down Piney Point and the number of activities undertaken by volunteers in our community are moving us in the right direction. Failures with our aging wastewater infrastructure, illegal mangrove trimming, dumping grass clippings into storm drains, not picking up after our pets and overfertilization of our landscapes by private homeowners are moving us in the wrong direction. The future health of this bay is up to us as a community making more right moves than wrong ones.